Too Many Priorities Is No Priorities

Years ago, I participated in a strategic planning exercise. We did everything right — or at least everything the experts told us to do. There were sticky notes. There were breakout sessions. There was a detailed process with frameworks and dot-voting.

We emerged with thirteen strategic initiatives.

Thirteen.

I tried to salvage it by grouping them into categories, hoping that three or four buckets would be more manageable and memorable than thirteen scattered items. It helped a little. But I left that exercise feeling like we’d skipped the real work — the hard work of deciding what actually mattered most.

Sound Familiar?

That experience wasn’t unique. It’s a common trap: a planning session generates a dozen “strategic priorities.” Everyone feels good. Every constituency got something on the list. Nobody had to make the hard call.

And then nothing gets done.

It’s easier to add than to subtract. Saying “this is important” costs nothing. Saying “this is more important than that” costs something — it means telling someone their thing didn’t make the cut.

So we avoid the conflict. We keep adding. We call it “comprehensive strategy” when it’s really strategic abdication.

What Priority Actually Means

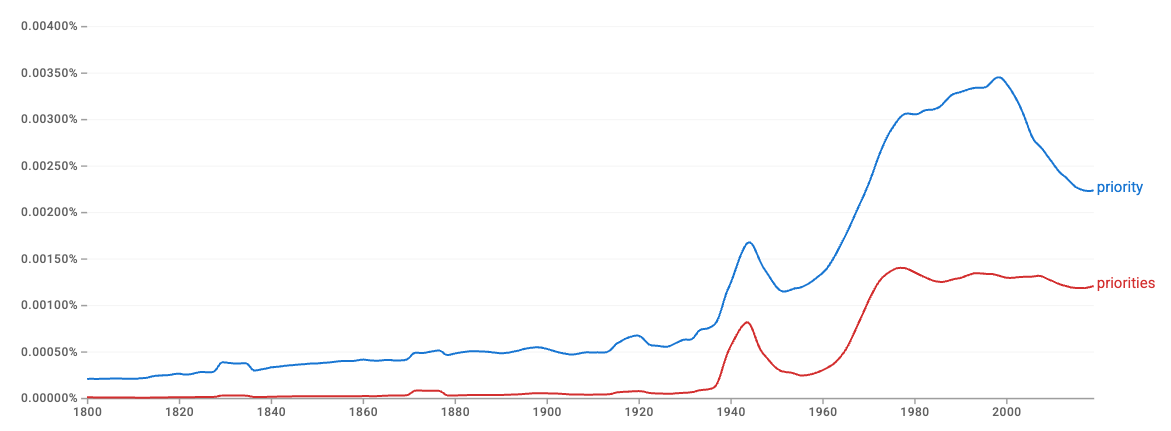

The word “priority” came into English in the 1400s. It meant the state of being first — singular by definition. You had a priority. The plural form “priorities” was grammatically possible but barely used for centuries. Google’s Ngram data shows it was nearly nonexistent in print until the 1940s, when it suddenly took off. We’ve been diluting the concept ever since.

Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer

Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer

If everything is a priority, nothing is. That’s just math. Teams have finite time and attention. The energy isn’t unlimited either. Twelve equally important things means zero important things.

Now AI Is Making It Worse

I’m watching a new flavor of this problem emerge.

The old version was too many priorities — political aggregation, everyone’s wish on the list. The new version is too many possibilities. AI keeps opening doors that used to be closed. Things that weren’t feasible last year are feasible now. The menu of “things we could do” expands every month.

The temptation is obvious: “We couldn’t do X before, but now we can! Let’s add it to the roadmap.”

Multiply that by twenty different X’s and you’ve got the same thirteen-initiative problem — except now it feels justified because the capabilities are real.

But “can do” isn’t the same as “should do.” AI makes execution cheaper. That means the quality of your decisions matters more, not less. Getting the wrong answer faster isn’t progress.

When everything becomes possible, discernment becomes the differentiator.

The Real Test

One way I’ve learned to spot real priorities: look at what got stopped.

Focus requires sacrifice. Every genuine priority implies things that aren’t priorities — things you’re deliberately not doing, or doing with less energy, or doing later.

If your priority list grew but nothing got cut, you didn’t prioritize. You aggregated.

Why Three

If thirteen is too many, what’s the right number? I’ve landed on three as a working limit. There’s science behind this — research on working memory suggests we can hold about four items in active attention at once. Some older studies say seven, but even that’s generous. Three is small enough to fit in your head without effort. Small enough to survive an elevator pitch. Small enough that you don’t need to check a document to remember what you’re focused on.

More importantly, three forces choice. Every constituency can’t be satisfied with three. Someone’s thing won’t make the list — and that’s the whole point.

How to Get There

A question that helps: If you could only accomplish one thing this year, what would it be?

One. Not three. One.

Get agreement on that, then ask: What’s the second most important thing? Then the third. Stop there.

Everything else goes on a “not now” list. Not “not important” — just “not now.” That distinction matters. It acknowledges value without pretending you can do everything at once.

But even “not now” lists need discipline.

The Barnacle Problem

In a product management presentation I give, there’s a section called “How to Be Ruthless.” One of the hardest parts: dealing with the “eventually” items.

If something doesn’t have immediacy — if the best you can say is “we’d like to do this eventually” — you’re better off removing it from the list entirely. Those items function like barnacles on a ship’s hull. They don’t sink you, but they slow you down. Every time you review the backlog, you spend a little energy on them. Every planning session, someone asks about them. They create drag.

The counterintuitive part: if something is truly important, it will rise to the top when the time is right. You don’t need to keep it on the list to remember it. Removing it now doesn’t mean it’s gone forever — it means you’re not paying the carrying cost until it actually matters.

A backlog that stretches far into the future isn’t a plan. It’s a guilt list.

Looking back at those thirteen strategic initiatives? I’d bet at least eight of them were barnacles. Items that felt important enough to include but never important enough to actually do. We would have been better off never writing them down.

The Liberation of Less

Ruthless prioritization feels good. Teams that know what they’re doing — and what they’re not doing — operate with clarity.

The context-switching stops. So does the relitigating in every meeting. Progress actually starts.

There’s something liberating about less. Especially now, when AI whispers that you could do more.

AI can tell you how to do things. It can’t tell you which things are worth doing. That’s still your job.